Since the Angle-Case debate of the early 20th century, orthodontists have been arguing about nonextraction therapies vs. extraction treatment plans. This is a debate that has continued for more than 100 years and probably will continue far into the future. However, there are some very real reasons that today’s orthodontists still recommend the extraction of teeth. Currently, most orthodontists pursue nonextraction treatment plans for patients first, and then extract only when confronted with the following clinical problems:

Reasons to extract:

1. Tooth mass – arch length discrepancy (severe crowding)

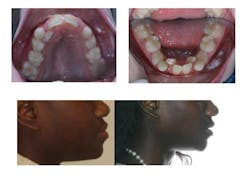

Severe crowding is the easiest of these conditions to determine. In a growing patient, this can be manifested with impacted incisors and/or canines. Most of these cases become tooth replacement because there is not enough room for teeth to erupt.

2. Bimaxillary dentoalveolar protrusion

Bimaxillary dentoalveolar protrusion has become more acceptable in today’s esthetic and functional viewpoint. By looking at the fashion magazines and celebrities of the today, this appearance is more desirable. However, if someone’s teeth are too protrusive, the extraction of teeth remains the best orthodontic treatment to reduce this issue.

ALSO BY DR. ZACKARY FABER |Orthodontics: It's not just cosmetics

3. Skeletal disharmony and camouflage treatment

In nongrowing patients (adults and older adolescents), the extraction of premolars remains a mechanotherapy to correct maxillary protrusion by retracting the maxillary incisors. In addition, patients who have moderate crowding and Class II occlusions can be successfully treated with the extraction of four bicuspids in order correct these problems. Most of us recognize a Class III mandibular prognathism as a surgical case; the same should be said about the Class II mandibular retrognathic patient. Extraction of teeth and retraction of the incisors in the mandibular retrognath can contribute to future health issues in some patients who might already have breathing issues. Lastly, there are some instances where an orthodontist will extract teeth in a surgical case to allow for the decompensation of the incisors or to remove the necessity for a surgically assisted expansion (SARPE), a second surgical procedure.

4. Efficiency of treatment?

In select cases, it might benefit the patient and the orthodontist to extract bicuspids in lieu of pursuing the nonextraction treatment plan. Orthodontists can only create space by distalizing molars, expanding arches, and flaring incisors. If we do all three of these things, some patients might be in the bimaxillary dentoalveolar protrusion scenario, and some patients do not respond to the nonextraction mechanics that we may think we can provide. Even if we make room for the bicuspids, the nonextraction treatment plan could add months or years to the case.

There are many reasons for an orthodontist to recommend extractions or nonextraction treatment in patients. This might also be the best time to discuss treatment philosophy or goals with your referring orthodontists. Education of ourselves and for our patients should be paramount, and all of the dentists and specialists should understand the reasoning for different treatment plans for different patients.

ALSO BY DR. ZACKARY FABER |Everything you need to know about CBCT in dentistry

Careful diagnoses and treatment planning of each individual’s specific problems leads the orthodontist to an individualized plan to create that person’s authentic smile. As always, the patient (and parents) must also be included in the planning stages due to the goals of the case. Only by setting individual objectives for each case can the orthodontist establish goals that will provide a beautiful, functional, and hopefully stable occlusion for each patient.