Sjögren's syndrome: Considerations during and after cosmetic dentistry

Sjögren's syndrome is an autoimmune condition that affects the body’s moisture-producing glands.1 It is the third most common rheumatic disorder after rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus.2 Sjögren's is often identified by its two most common symptoms—dry eyes and dry mouth. Other symptoms can include profound fatigue, chronic pain, major organ involvement, neuropathies, and increased incidence of lymphomas (5%). The prevalence occurs in up to 3% of the population.

The mechanism underlying the development of Sjögren's is the destruction of the epithelium of the exocrine glands, as a consequence of abnormal B cell and T cell responses to autoantigens.3 The disease was described in 1933 by Swedish Ophthalmologist Dr. Henrik Sjögren, after whom it is named; however, a number of earlier descriptions of people with the symptoms exist. Between 0.2% and 1.2% of the population are affected with this autoimmune disease, with half having the primary form and half the secondary form. Females are affected about 10 times as often as males, and the disease commonly begins in middle age with a mean age of diagnosis at 54.4 The prognosis is largely dependent on systemic components, with pulmonary involvement resulting in a two- to four-times greater mortality risk.4

Sjögren's can be difficult to diagnose, because the symptoms can mimic those caused by other diseases. Diagnosis requires a number of clinical and pathological features. Blood tests for antibodies, eye tests for dryness, and imaging or biopsy of salivary glands can be used for a final diagnosis. Dentists and oral pathologists serve an important role in diagnosis, since common diagnostic criteria include adequate biopsy of minor salivary glands. Lymphocytic focal sialadenitis, which describes the presence of dense aggregates of lymphocytes, is consistent with Sjögren's syndrome.5

Case study

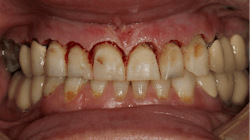

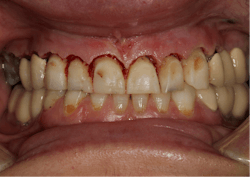

A 35-year-old female patient presented with esthetic concerns after a diagnosis of Sjögren's syndrome. Patient complaints included short appearance of teeth, stained teeth, and worn incisal edges (figures 1–2). Loss of vertical dimension of occlusion was noted as evidenced by shortened coronal structure and bilateral angular cheilitis (figure 3).

Upon clinical and radiographic examination, it was determined that the patient had a combination of caries, inflamed gingiva from desiccation, and loss of vertical dimension (figure 4). Xerostomia and insufficient home care were implicated in the patient’s elevated caries rate, as well as the presence of implants leading to implant-induced caries.

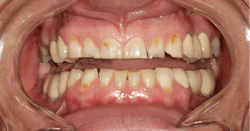

After the first phase consisting of caries control and periodontal treatment, the patient received soft- and hard-tissue crown lengthening by laser (figure 5). After an eight-week healing period, full-mouth cosmetic restorations were placed, which included full- and three-quarter-coverage e.max crowns and zirconia bridges (figures 6–7).

Following therapy, the patient was seen every three months for hygiene recare and to evaluate the status of caries and gingival inflammation. CariFree CTx4 Gel, home-administered sodium fluoride trays, and interproximal irrigators were given to the patient to increase resistance to caries. Oral hygiene instruction was an integral part of the recare visits and proved to be valuable in maintaining the patient’s results two-and-a-half years later (figure 8).

All photos courtesy of the authors.

Editor’s note: This article originally appeared in Perio-Implant Advisory, a newsletter for dentists and hygienists that focuses on periodontal- and implant-related issues. Perio-Implant Advisory is part of the Dental Economics and DentistryIQ network. To read more articles, visit perioimplantadvisory.com and subscribe at this link.

References

- What is Sjögren’s syndrome? National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal Skin Diseases. Reviewed September 2016. https://www.niams.nih.gov/health-topics/sjogrens-syndrome

- Tanakchi S, Aly FZ. Sjögren’s syndrome. PathologyOutlines.com. October 1, 2015. Updated March 12, 2020. https://pathologyoutlines.com/topic/salivaryglandsgren.html

- Brito-Zerón P, Baldini C, Bootsma H, et al. (7 July 2016). Sjögren syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16047. doi:10.1038/nrdp.2016.47

- Brito-Zerón P, Kostov B, Solans R, et al. Systemic activity and mortality in primary Sjögren syndrome: predicting survival using the EULAR-SS Disease Activity Index (ESSDAI) in 1045 patients. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(2):348-355. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-206418

- Fisher BA, Jonsson R, Daniels T, et al. Standardisation of labial salivary gland histopathology in clinical trials in primary Sjögren's syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis.2017;76(7):1161-1168. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210448

About the Author

Scott Froum, DDS

Editorial Director

Scott Froum, DDS, a graduate of the State University of New York, Stony Brook School of Dental Medicine, is a periodontist in private practice at 1110 2nd Avenue, Suite 305, New York City, New York. He is the editorial director of Perio-Implant Advisory and serves on the editorial advisory board of Dental Economics. Dr. Froum, a diplomate of both the American Academy of Periodontology and the American Academy of Osseointegration, is in the fellowship program at the American Academy of Anti-aging Medicine, and is a volunteer professor in the postgraduate periodontal program at SUNY Stony Brook School of Dental Medicine. He is a trained naturopath and is the scientific director of Meraki Integrative Functional Wellness Center. Contact him through his website at drscottfroum.com or (212) 751-8530.

Alisa Neymark, DDS

Alisa Neymark, DDS, graduated with a Bachelor of Arts in anthropology and biology from Amherst College, and then pursued her dental degree at Stony Brook School of Dental Medicine. Upon completion of a two-year residency at Long Island Jewish Medical Center, she has been in private practice both on Long Island and in Brooklyn. Dr. Neymark practices with an emphasis on cosmetic dentistry and restoring implants.