Herpes labialis, also known as cold sores, is a common viral infection of the lips or mouth area caused by the herpes simplex virus. It is characterized by the appearance of one or more small, painful blisters or lesions on or around the lips. Symptoms may include ulcerations, itching, burning, or tingling around the mouth, and swollen lymph nodes.

Recurrent herpes labialis is a global lifelong oral health problem for patients and dental professionals that has yet to have a cure. It affects approximately one-third of the world’s population, causing episodes of pain and discomfort upon vesicular blistering. It can cause individuals to feel socially restricted as the lips are compromised esthetically, and some may feel culturally stigmatized.

Antiviral drugs such as acyclovir, penciclovir, and valacyclovir in cream or tablet form have not been successful in eliminating the virus or its recurrence. Currently, different kinds of laser treatment, wavelengths, and protocols have been proposed for the management of recurrent herpes labialis. Here, I’ll briefly review and provide a case example of how low-level laser therapy (LLLT) can be used to reduce the time and severity of herpes labialis infections.

Diseases most likely to affect the tongue and the importance of proper examination and diagnosis

What is low-level laser therapy and how does it work?

LLLT is a type of medical treatment that uses lasers or light-emitting diodes to stimulate cells in the body and promote healing. This treatment is sometimes referred to as cold laser therapy or soft laser therapy. It is used to treat a variety of medical conditions, including chronic pain, hair loss, and wound healing. LLLT has also been used to prevent or shorten herpes labialis outbreaks.

It works by delivering low levels of laser energy (usually in the range of 5–80 watts) to the target area, which is absorbed by the body’s cells.1 The cells then convert the energy into biochemical energy, which is used to repair damaged cells and stimulate the growth of new, healthy cells.

What the science says about LLLT

A review of the literature to find successful protocols, and their indications regarding the effects of laser irradiation on recurrent herpes labialis, shows mostly heterogenous case examples with the need for double-blinded, controlled clinical trials. Many case studies that evaluate the effects on healing time, pain relief, duration of viral shedding, viral inactivation, and interval of recurrence show that although LLLT can’t completely eliminate the virus and its recurrence, it can decrease pain, time of outbreak, and the interval of recurrences without causing any side effects.2 It can be helpful in reducing severity of onset in the prodromal phase (before the lesion occurs), viral titer in the vesicle phase, and may assist with drainage and resolution in the crust phase.3 A major benefit of this laser therapy is that it can be combined with antiviral therapy and other topical lip ointments to further decrease chances of onset, duration time, severity, and associated pain.4

Safe use of LLLT

When using lasers or electrosurgical units, concerns have been raised regarding aerosolization of virus particles and transmission potential.5 Good practice would call for the use of high-speed evacuation (HVE) during laser use with minimal use of air/water spray to mitigate this potential.6 One large patient-based study showed that even in the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, with the use of HVE, proper personal protective equipment, and extraoral suctions (EOS), no viral transmission was noted during any dental procedure, including laser ablation.7

Clinical case

This case example describes a 54-year-old female with an otherwise noncontributory medical history. The patient was taking no medications with no stated allergies and had a history of severe recurrent herpes labialis outbreaks. She experienced this “cold sore outbreak” 13 days ago and the pain had increased in intensity. She demonstrated crusting on her lips with ulceration (figure 1).

A Solea laser (Convergent Dental) 9.3-micron CO2 laser was used at the lower power setting of 1.25 mm spot size, 20% cutting speed emitting 0.7 watts.8 With the use of HVE and an EOS (figure 2), the lesion was lased for 60 seconds in a triple-pass fashion (figure 3).

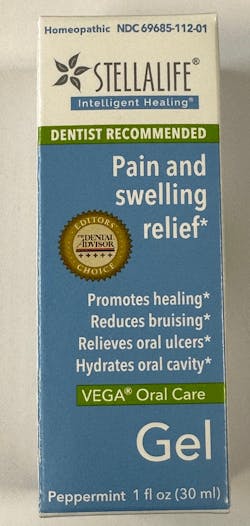

StellaLife Vega Oral Care Gel (StellaLife) was applied to the lesion and given to the patient with instructions to apply the gel to the area three times a day (figure 4). The patient returned four days later with approximately 80% of the lesion showing resolution and 90% pain reduction (figure 5).

Editor’s note: This article originally appeared in Perio-Implant Advisory, a chairside resource for dentists and hygienists that focuses on periodontal- and implant-related issues. Read more articles and subscribe to the newsletter.

References

- Al-Maweri SA, Kalakonda B, AlAizari NA, et al. Efficacy of low-level laser therapy in management of recurrent herpes labialis: a systematic review. Lasers Med Sci. 2018;33(7):1423-1430. doi:10.1007/s10103-018-2542-5

- Barros AWP, Sales PHDH, Silva PGDB, Gomes ACA, Carvalho AAT, Leão JC. Is low-level laser therapy effective in the treatment of herpes labialis? Systematic review and meta-analysis. Lasers Med Sci. 2022;37(9):3393-3402. doi:10.1007/s10103-022-03653-6

- Khalil M, Hamadah O. Association of photodynamic therapy and photobiomodulation as a promising treatment of herpes labialis: a systematic review. Photobiomodul Photomed Laser Surg. 2022;40(5):299-307. doi:10.1089/photob.2021.0186

- Moskvin SV. Low-level laser therapy for herpesvirus infections: a narrative literature review. J Lasers Med Sci. 2021;12:e38. doi:10.34172/jlms.2021.38

- Manson LT, Damrose EJ. Does exposure to laser plume place the surgeon at high risk for acquiring clinical human papillomavirus infection? Laryngoscope. 2013;123(6):1319-1320. doi:10.1002/lary.23642

- Moreira LB, Sanchez D, Trousdale MD, Stevenson D, Yarber F, McDonnell PJ. Aerosolization of infectious virus by excimer laser. Am J Ophthalmol. 1997;123(3):297-302. doi:10.1016/s0002-9394(14)70124-2

- Froum SH, Froum SJ. Incidence of COVID-19 virus transmission in three dental offices: a 6-month retrospective study. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2020;40(6):853-859. doi:11607/prd.5455

- Froum SH, Cantor-Balan R, Kerbage C, Froum SJ. Thermal testing of titanium implants and the surrounding ex-vivo tissue irradiated with 9.3um CO2 Implant Dent. 2019;28(5):463-471. doi:10.1097/ID.0000000000000923

About the Author

Scott Froum, DDS

Editorial Director

Scott Froum, DDS, a graduate of the State University of New York, Stony Brook School of Dental Medicine, is a periodontist in private practice at 1110 2nd Avenue, Suite 305, New York City, New York. He is the editorial director of Perio-Implant Advisory and serves on the editorial advisory board of Dental Economics. Dr. Froum, a diplomate of both the American Academy of Periodontology and the American Academy of Osseointegration, is in the fellowship program at the American Academy of Anti-aging Medicine, and is a volunteer professor in the postgraduate periodontal program at SUNY Stony Brook School of Dental Medicine. He is a trained naturopath and is the scientific director of Meraki Integrative Functional Wellness Center. Contact him through his website at drscottfroum.com or (212) 751-8530.