Predictable halitosis treatment: Using microbial testing and antibiotic rinse therapy

Treatment of patients with breath concerns is a difficult process, because no formal training currently exists in dental or dental hygiene schools. The perception of halitosis is that it is related to poor oral hygiene or due to a medical concern. However, oral bacteria—mainly periodontal pathogens—are the most common cause of halitosis.

Bacteria use amino acids and then produce volatile sulfur compounds (VSCs) as a metabolic by-product. The reality is that even healthy-looking mouths can have breath odor caused by bacteria, because the inflammatory response appears to be minimal. The problem is not limited by age or dentition. In our practice, we have treated three-year-old children and older edentulous patients for halitosis. It is not uncommon for us to see a patient whose oral tissues appear healthy but who has substantial mouth odor.

ADDITIONAL READING |Increasing dental case acceptance through the use of salivary diagnostics

The following is a case presentation of a patient referred to my office for breath care after his medical and dental providers could not resolve the issue.

Mr. LB was referred by his physician, because all of the medical treatments and tests did not resolve the problem. His dentist said it was not related to periodontal concerns. His wife would not kiss him, and coworkers kept their distance because of the strong oral odor. His tonsils were removed two years ago due to repeated infections, and his stomach ulcer was treated with antibiotics. Scoping the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum showed no irregularities.

We tested his VSC content using a portable gas chromatograph, the OralChroma (FIS Inc.). Readings were: hydrogen sulfide: 88ppb; methyl mercaptan: 23ppb; dimethyl sulfide: 8ppb. Baseline is: < 122ppb; < 26ppb; < 6ppb, respectively.

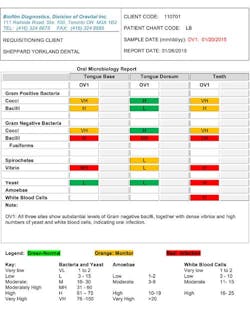

This objective test showed gases were present just below threshold, but in combination indicated breath odor. Organoleptic testing detected interproximal odors as well from the tongue base and tongue dorsum at 4 out of 5 for all sites. Biofilm samples were taken from the tongue dorsum and base, and between the teeth (see chart below). The clinical examination showed 23 bleeding points and pockets < 3 m. However, there was severe generalized bleeding with the Papillary Bleeding Score. Saliva pH was 8.0, a reading that occurs with periodontal disease and breath odor. We used two-tone disclosing solution to identify biofilm and demonstrated brushing at the gingival margin, as well as using GUM Soft-Picks (Sunstar Americas, Inc.) instead of floss to clean the interproximal areas.

Based on the microbiology report, LB was prescribed an antibiotic rinse mixture of tetracycline and nystatin versus metronidazole/nystatin. Within three days, the patient reported that the bleeding had stopped and odors decreased. After two weeks of using the antibiotic rinse three times a day, LB was placed on 0.2% chlorhexidine twice a day for two weeks.

We reexamined LB and repeated the tests. The OralChroma readings were 000. There were no interproximal or tongue odors. Bleeding points were reduced to 3 and pH was normal (7.0). LB was asked to use a chlorine dioxide with xylitol mouthwash (Oravital CDLx, Oravital Inc.) as a component of his daily maintenance routine. LB is happy! He has no odors, and his wife is kissing him again. This therapy took two-and-a-half hours of hygiene time.

Breath odor is an emotional issue and is most often of bacterial origin. Treatment requires that both the psychological and causative aspects be considered. Objective measurements and microbial testing to identify the location of the infection followed by antibiotic rinse therapy are the essential components to treat predictably. This is a novel way of treating a problem many patients have, yet few dental professionals feel competent to treat.