Teeth with bone loss beyond the root apex: Can they be saved?

Bone loss to or beyond the radiographic apex of a natural tooth is considered to be hopeless by most periodontal classification schemes.1 Older, simple prognosis classification studies typically categorize teeth as being poor to hopeless and tooth extraction warranted when bone loss around a tooth is 50% or greater.2 A more recent complex classification scheme, released by the American Academy of Periodontology in collaboration with the European Federation of Periodontists, on the grading and staging of periodontal disease, suggests that a poor to hopeless long-term prognosis occurs when bone loss extends to or beyond the middle third of the tooth root.3

An interesting study evaluating the accuracy of simple versus complex models predicting tooth loss looked at 627 patients over an 18-year average and showed that no model was better at predicting tooth loss than others.4 A conclusion of this study was that many of these tooth classification schemes may not be useful in a clinical setting, and that true prognosis is practitioner-/patient-specific. The practitioner often relies on clinical experience and therapeutic familiarity when deciding whether to extract periodontally involved teeth and replace them with dental implants versus saving the natural dentition with regenerative therapy. Part of this decision matrix of save versus extract should be patient desire and long-term cost-effectiveness to the patient.

Do teeth with severe periodontal disease cause bone loss around adjacent teeth?

It depends.

Retention of severely periodontally compromised teeth with initial, surgical, and supportive therapy has been shown to have high long-term success rates in the literature.5 However, keeping teeth with advanced bone loss, without performing periodontal treatment on them, will have a negative effect on the adjacent teeth and can cause bone loss at a rate 10 times higher than if they were extracted.6

With that being said, even teeth with 70% or more bone loss were able to be saved long term with no detrimental effect on the adjacent proximal teeth if periodontal treatment was performed on the “hopeless teeth.”7 In fact, an eight-year study on “hopeless teeth” postperiodontal treatment showed no further bone loss around those teeth and no bone loss on teeth adjacent to the hopeless teeth.8

Can teeth with complete bone loss around the apex be saved?

Yes.

A large, randomized controlled trial of 50 patients presenting with advanced bone loss and at least one hopeless tooth to be extracted due to periodontal bone loss were enrolled in a study. The hopeless teeth evaluated had bone loss to or beyond the apex of the tooth. Twenty-five hopeless teeth were periodontally treated with a regenerative strategy, and 25 teeth were extracted and replaced with either a fixed bridge or a dental implant. Two teeth in the “save the teeth” group were lost in the first year. At the end of five years, the remainder of the teeth in the “save the teeth” group (23 out of 25 regenerated teeth) showed clinical improvement. Clinical attachment level gains were around 8 mm, radiographic bone gain around 8.5 mm, and probing depth reduction about 9 mm. Residual pocket depths around the once-hopeless teeth were about 4 mm.9

This same group was then evaluated for another five years of the 10-year study. All teeth not lost after the first year (23 out of 25) were still present and remained clinically stable. The 10-year clinical attachment gain was 7 mm, residual pockets were about 3.5 mm, and saving the teeth was a less costly alternative to tooth extraction and replacement.

The study concluded that the complexity of treatment, technical skill needed to perform the treatment, and patient compliance needed to maintain this result (patients reported every three months for hygiene during the duration of the study) limit its widespread application. This study was proof of principle that hopeless teeth with bone loss to or beyond the tooth apex can be saved with long-term predictability.10

Steps involved in saving teeth with bone loss around the tooth apex:

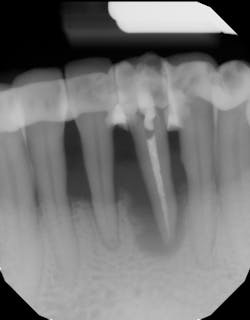

- Ensure tooth does not have a root fracture and check/refer for endodontic treatment if tooth is nonvital (figure 1)

- Splint tooth and adjust occlusion11 (figure 2)

- Proper surgical technique including incision, flap design, and complete detoxification of bony defect and root apices (figures 3 and 3a)

- Appropriate scaffolding material, biologic agent, and/or cell occlusive barrier for periodontal regeneration (figure 4)

- Primary closure without tension (figure 5)

- Follow-up hygiene appointments every three months or less to ensure long-term result (figures 6 and 6a)

When deciding between saving the severely compromised natural dentition and extracting/placing implants, there are many factors to consider. In addition to long-term success rates, the practitioner and the patient need to consider the long-term economic impact the patient will have to endure. Both dental implants and periodontal therapy to save natural teeth have high initial success rates, with implants usually slightly higher in initial costs. However, when looking at long-term retention rates, teeth often demonstrate fewer complications and have much less of a financial impact if correction is needed around the dental implant.

References

- McGuire MK, Nunn ME. Prognosis versus actual outcome. II. The effectiveness of clinical parameters in developing an accurate prognosis. J Periodontol. 1996;67(7):658-665. doi:10.1902/jop.1996.67.7.658

- McGuire MK. Prognosis versus actual outcome: a long-term survey of 100 treated periodontal patients under maintenance care. J Periodontol. 1991;62(1):51-58. doi:10.1902/jop.1991.62.1.51

- Caton JG, Armitage G, Berglundh T, et al. (2018) A new classification scheme for periodontal and peri-implant diseases and conditions—introduction and key changes from the 1999 classification. J Clin Periodontol. 2018;45(Suppl 20):S1-S8. doi:10.1111/jcpe.12935

- Krois J, Graetz C, Holtfreter B, Brinkmann P, Kocher T, Schwendicke F. Evaluating modeling and validation strategies for tooth loss. J Dent Res.2019;98(10):1088-1095. doi:10.1177/0022034519864889

- Levin L, Halperin-Sternfeld M. Tooth preservation or implant placement: a systematic review of long-term tooth and implant survival rates. J Am Dent Assoc. 2013;144(10):1119-1133. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.2013.0030

- Machtei EE, Zubrey Y, Yehuda AB, Soskolne WA. Proximal bone loss adjacent to periodontally “hopeless” teeth with and without extraction. J Periodontol. 1989;60(9):512-515. doi:10.1902/jop.1989.60.9.512

- Machtei EE, Hirsch I. Retention of hopeless teeth: the effect on the adjacent proximal bone following periodontal surgery. J Periodontol. 2007;78(12):2246-2252. doi:10.1902/jop.2007.070125

- Wojcik MS, DeVore CH, Beck FM, Horton JE. Retained “hopeless” teeth: lack of effect periodontally-treated teeth have on the proximal periodontium of adjacent teeth 8-years later. J Periodontol. 1992;63(8):663-666. doi:10.1902/jop.1992.63.8.663

- Cortellini P, Stalpers G, Mollo A, Tonetti MS. Periodontal regeneration versus extraction and prosthetic replacement of teeth severely compromised by attachment loss to the apex: 5-year results of an ongoing randomized clinical trial. J Clin Periodontol. 2011;38(10):915-924. doi:10.1111/j.1600-051X.2011.01768.x

- Cortellini P, Stalpers G, Mollo A, Tonetti MS. Periodontal regeneration versus extraction and dental implant or prosthetic replacement of teeth severely compromised by attachment loss to the apex: a randomized controlled clinical trial reporting 10-year outcomes, survival analysis and mean cumulative cost of recurrence. J Clin Periodontol. 2020;47(6):768-776. doi:10.1111/jcpe.13289

- Amid R, Kadkhodazadeh M, Dehnavi F, Brokhim M. Comparison of stress and strain distribution around splinted and non-splinted teeth with compromised periodontium: a three-dimensional finite element analysis. J Adv Periodontol Implant Dent. 2018;10(1):35-41. doi:10.15171/japid.2018.007

About the Author

Scott Froum, DDS

Editorial Director

Scott Froum, DDS, a graduate of the State University of New York, Stony Brook School of Dental Medicine, is a periodontist in private practice at 1110 2nd Avenue, Suite 305, New York City, New York. He is the editorial director of Perio-Implant Advisory and serves on the editorial advisory board of Dental Economics. Dr. Froum, a diplomate of both the American Academy of Periodontology and the American Academy of Osseointegration, is in the fellowship program at the American Academy of Anti-aging Medicine, and is a volunteer professor in the postgraduate periodontal program at SUNY Stony Brook School of Dental Medicine. He is a trained naturopath and is the scientific director of Meraki Integrative Functional Wellness Center. Contact him through his website at drscottfroum.com or (212) 751-8530.