To splint or not to splint adjacent implants: A 10-year retrospective analysis

Splinting of adjacent implants in segmental tooth replacement has been a controversial issue. In contrast to full implant-supported fixed prostheses, where splinted implants are accepted as means of support, in segmental reconstructions involving two or three adjacent implants there is a tendency to equate implants to natural teeth. Unless specifically indicated due to pathologic mobility, it is accepted that restored natural teeth should not be splinted for both biological and mechanical considerations. Ease of hygiene and good marginal fit of prostheses are more predictable around nonsplinted teeth.

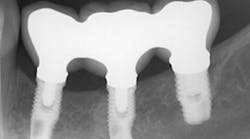

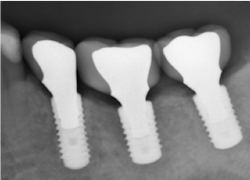

The same arguments have been advanced for not splinting adjacent implants in segmental reconstructions (figure 1). Plaque-related peri-implantitis is the most common biological complication in implant dentistry. A passive fit of prostheses on their supporting implants is considered essential for minimizing mechanical and biological overloading. On the other hand, it is also claimed that splinting can prevent overloading (figure 2). Screw loosening and fracture of veneering material are the most common mechanical complications of loading, although there is little evidence that it results in loss of integration.

Figure 1: Nonsplinted adjacent implants

Figure 2: Splinted adjacent implants

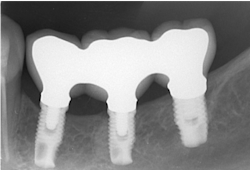

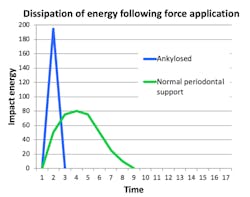

Implants are not tooth analogues. They are foreign bodies that can maintain a biological equilibrium in the surrounding hard and soft tissues. The most significant differences to teeth relate to their lack of resilience, due to their ankylosed state, and reduced proprioceptive feedback, essential for modulating occlusal forces (figure 3). However, the remaining teeth in segmental reconstructions can usually compensate for the latter.

Figure 3

Is this lack of resilience an important consideration when considering splinting of adjacent implants, and do any mechanical or other advantages outweigh the perceived problems of hygiene capacity and lack of passive fit?

Additional factors to consider include:

- Will splinting further affect resilience and peak energy loads generated by occlusal forces?

- Can splinting decrease the incidence of fracture/chipping of veneering porcelain in bilaminar constructions?

- Can splinting minimize screw loosening?

- Can splinting reduce micromotion and associated corrosion?

- Can splinting affect failure of biological and nonbiological structures?

- Can splinting reduce the need for augmentation procedures to affect adequate support and esthetics in some reconstructions?

- Can splinting enhance intraoral handling and repair of reconstructions?

A biomechanical rationale can be outlined for minimizing mechanical complications by splinting of adjacent implants in segmental reconstructions, while arguing that with adequate design and laboratory procedures, effective hygiene and passive fit can be achieved. Other advantages add further weight to this protocol.

Loss of interdental papilla after extraction can be compensated for with pink porcelain when adjacent implants are splinted. Also, splinting can simplify clinical procedures and enhance esthetics (figure 4).

Figure 4: Esthetic considerations

Splinting can be an advantage when adjacent implants fail. If multiple adjacent implants are splinted, prosthetic reconstruction of the implant bridge can be done if one or more implants fail. This is a more noninvasive approach than having to remove then entire prosthesis and fabricate a new one. As seen in Figure 5, a three-unit splinted implant-supported bridge was removed and minimally altered when the middle implant failed. The remaining implants were used to reinsert the prosthesis instead of an entirely new bridge having to be reconstructed.

Figure 5: Reconstruction of splinted implants

Author's note: Dental professionals can hear Dr. Walton’s full presentation on this topic, 10 Years After: To Splint or Not to Splint Adjacent Implants?, by attending the Academy of Osseointegration’s 2019 Annual Meeting. The meeting, Current Factors in Clinical Excellence, will be held March 13–16, 2019, at the Walter E. Washington Convention Center in downtown Washington, DC. Dr. Walton will present his topic during the academy's Prosthetic Track—10 Years After session on Friday, March 15, 2019. Early-bird registration is available through January 14, 2019. For all the meeting details, including online registration, please go to https://ao2019.osseo.org/.