This month's clinical tip from the editor: After a tooth extraction, are you guilty of chucking the tissue?

There are many etiologies behind the development of a radiolucent lesion at the apex of a tooth root. What clinicians are most familiar with are lesions of endodontic origin. Most of the time a dentist will see a radiolucency at the apex of the tooth, hopefully will test for vitality as well as perform other diagnostic tests, and if the tooth is nonvital will perform the root canal or refer it to a specialist who will accomplish this treatment. There are times, however, that tooth vitality is not checked and root canal treatment is simply initiated. The problem with this approach is that if the lesion is of nonendodontic origin, this treatment will not resolve the problem, and the lesion can expand in size even after the root canal is completed. These teeth can then be referred for apicoectomy or extraction with subsequent implant placement because of perceived root canal failure. Once again, because of improper diagnosis, these aggressive treatments may not take care of the original etiology behind the lesion.

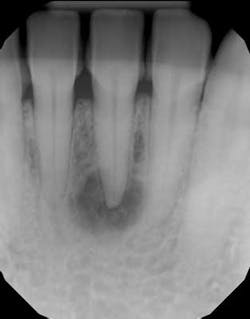

Radiographic bone changes that mimic lesions of endodontic origin can include neoplasms as well as developmental alterations. (1) The differential diagnosis behind a unilocular radiolucent lesion that can look like a typical periapical radiolucency (PAR) of endodontic origin includes: periapical cemento-osseous dysplasia (figure 1), ameloblastoma, odontogenic keratocyst, central giant cell granuloma, traumatic bone cyst, and central ossifying fibroma.

So what does all this mean? According to the chief of oral pathology at Mt. Sinai Hospital, Dr. Naomi Ramer, “Don’t just chuck the tissue after tooth extraction or apicoectomy.” She goes on to say, “Especially in the cases where you do not know the history of the tooth, when extracting teeth with periapical lesions, or after you curette this tissue out of the lesion during apicoectomy, you may want to consider sending the cystic tissue in for biopsy to determine the lesion’s origin.”

Why is this important?

Imagine this scenario: A dentist notices a radiographic radiolucency at the apex of a tooth during an exam and improperly initiates root canal therapy without taking the necessary diagnostic steps (vitality test, CBCT, clinical evaluation, etc.) on a tooth with an etiology other than endodontic origin. The lesion doesn’t resolve and the decision is made to extract the tooth with subsequent implant therapy. The implant is placed, and a few months later, an expanding radiolucency is now noted at the base of the implant. The implant is now deemed a failure with subsequent removal and regrafting.

This scenario doesn’t necessarily have to happen; however, it does illustrate that with proper diagnostics, the aforementioned treatment could have been avoided.

The moral of the story, according to Dr. Ramer, is when you don’t know why the tooth is exhibiting a lesion, don’t chuck the tissue after extraction. Instead, send it in for histopathologic testing!

MORE CLINICAL TIPS FROM DR. SCOTT FROUM …

This month's clinical tip from the editor: 'Help! My implant fell out!'

This month's clinical tip from the editor: 'How much do you charge for an implant? I just want to know the price!'

This month’s clinical tip from the editor: ‘The implant you put in my mouth is now bleeding; what should I do?’

Reference

1. Malek M et al. Differential diagnosis of a periapical radiolucent lesion. NYSDJ. 2015;81(5).